Recently Brazil experienced a flood in its southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul (RGS) that left almost 600,000 people displaced, 77,000 rescued, 800 injured and 169 dead (see official data here). It’s a terrible tragedy that has mobilized the nation.

Learn more in the Washington Post’s excellent photo essay and you can make donations (also from abroad) to SOS Rio Grande do Sul.

Now everyone is asking: why did this happen? and what can we do to prevent it in the future? The loudest answers are ‘climate change’ and ‘fight climate change!’, nationally and internationally.

But is climate the main villain of this story? The answer, I argue, is no.

Let me be clear: anthropogenic climate change is real, serious and merits committed investment in mitigation and adaptation. I do not discredit climate change as a fact, my contention is that climate change doesn’t play a role, let alone a leading role, in every weather disaster and specifically not the leading role in RGS floods.

The causes

The images of both catastrophe and incredible Brazilian solidarity in Rio Grande do Sul floods are gut punching, rivaling fiction. There are helicopter rescues, heroic volunteers, a horse stranded on a rooftop, professional big wave surfers on jet ski’s dodging crocodiles and man-eating piranhas.

These could be scenes in a movie. While, sadly, there is nothing fictitious about this tragedy, cinematic art can help us think through the cause of the floods.

If the Brazilian floods were a movie and the flood origins were personified by actors, the Oscars would nominate best actresses and supporting actors. Even when there are many protagonists, only one is chosen and nominated as the lead actress/actor. What cause plays the leading role in recent Brazilian flooding? Is climate the lead actor?

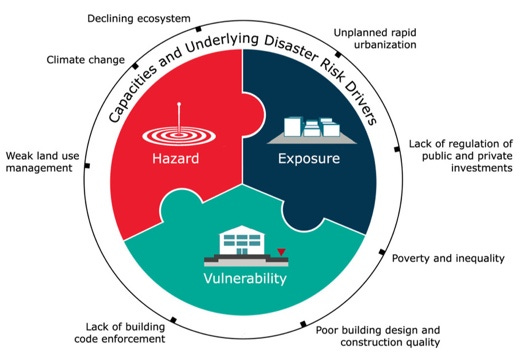

The cast of characters in a disaster is well established, comprised of components and their associated drivers. Any natural disaster is comprised of three components: the hazard, exposure and vulnerability. Each component in turn is affected, or motivated, by drivers.

Let’s call components and drivers the actors in our cinematic metaphor. In the case of Rio Grande do Sul, the hazard is flooding. And if you listen to the media, climate change is the principal driver of Brazilian floods - a lead actor monomaniacally driven by climate obsession.

In fact, according to disaster science, the hazard (flooding in this case) alone does not a disaster make.

Right now, there could be tremendous flooding in an uninhabited part of the Amazon or a record earthquake in Antarctica – an extreme hazard - yet no disaster. The hazard must affect exposed human beings and human property to cause damage, and thus become a disaster.

Finally, exposure (to a hazard) itself does not make a disaster. The disaster is dependent on the vulnerability of exposed people and property. The lighthouse in Port Bruce, Canada, for example is routinely exposed to fierce waves yet it is well constructed and remains largely invulnerable to decades of powerful hazards.

Now that we know the cast of characters, let’s identify a protagonist. First, the facts.

The facts

On April 21 2024, MetSul alerted that heavy rains were expected in Brazil’s southernmost State of Rio Grande do Sul (population: 11 million). Days later, MetSul warned about a possible 300mm of rain (the equivalent of 2 months) to happen in 1 week.

By April 27, parts of the state were starting to flood, including metropolitan Porto Alegre, the state’s largest city of 4.4 million people. On May 2 recorded rainfall in parts of the state reached between 500-700 mm in 5 days, unleashing the largest flood in regional history.

For comparison, 700 mm is about 28 inches. Colorado, where I live has an average annual precipitation of 18 inches. Hawaii - the wettest US state - has average of 63 inches or 1,600 mm of rain per year. In 5 days, it rained 10 inches more in parts of Rio Grande do Sul than Colorado’s annual average and just under half of Hawaii’s annual average.

The aftermath of the intense rain was tragic, and you can read a good summary in English here. Brazil is South America’s breadbasket, and Rio Grande do Sul is a major producer and exporter of agricultural products – over $1,1 billion was damaged.

The torrential rain landed on Rio Grande do Sul’s complex geography and hydrology. The largest city, Porto Alegre, is a port on a lagoon which is connected to the ocean. The Guaíba river reached 5.35m hight above its normal level on May 5, beating the record of 4.76m in the 1941 flood of Porto Alegre.

Sea level rise is unquestionably a result of climate change, so climate is a factor for coastal flooding. But flooding in RGS occurred throughout the entire state affecting 96% of all cities (471 of 497), and all of the watersheds, including regions miles away from the ocean. Among the few unaffected cities, four are on coastal watersheds and the coast itself (see map below). Sea level rise plays a role in RGS flooding, but cannot explain the mainland river flooding that affected most municipalities.

Climate science

I have a Master’s of Science and PhD in environmental studies and have studied climate change, and climate narratives, for more than a decade. Climate event detection and attribution has been evolving and is prominent in scientific reports, such as IPPC and U.S. National Climate Assessments, over the years and decades.

Let’s examine more carefully what the IPCC says about climate impact drivers of specific weather events. In a previous post I highlighted the IPCC table (WGI IPCC report pg. 1856) about climate impact driver’s (CID) for all weather events and corresponding detection and attribution.

As you can see, the IPCC has NO detection for changes in floods or landslides, and only expects mean precipitation to emerge by 2050 and heavy precipitation between 2050-2100. So the IPCC says climate change is NOT a driver detected for flooding or landslides, while it is a factor in greater precipitation.

Now, weather events are neither experienced in averages of space or averages of time, but locally in specific times and places. The IPCC CID table above gathers trends globally to tell a global story. Patrick Brown has a great post on climate change and flooding, which explains how and why the IPCC came to the conclusions above. I recommend his entire post and quote him below.

To be fair to southern Brazil, we need to look more carefully at the regional trends, which indeed tell a more nuanced climate story.

The IPCC does offer specifics on regional precipitation, flooding and landslides in chapter 12.4 of WGI report linked here. You can read about mean and extreme precipitation, landslides and flooding in Brazil for yourself in the IPCC report (southeast Brazil is designated as SES region), but it’s easier to visually show trends in the IPCC maps below.

1. Observed precipitation trends

From IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

You can see no significant trends for precipitation in southern Brazil for the IPCC’s latest report. Perhaps the precipitation event in Porto Alegre will be included in the next updated version of this report, but the records don’t show trends now.

2. Projected extreme precipitation

The IPCC shows climate model simulated changes in extreme precipitation and the range across models. The maps below not only show the median model change for 2°C of global warming in the middle panel but also the 5th percentile of the models in the left panel and the 95th percentile of the models in the right panel.

From IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

If we look carefully at the middle map (50th percentile), in a 2C warmer world (which is about where we are headed) we see greater rains expected for South and Southeast Brazil.

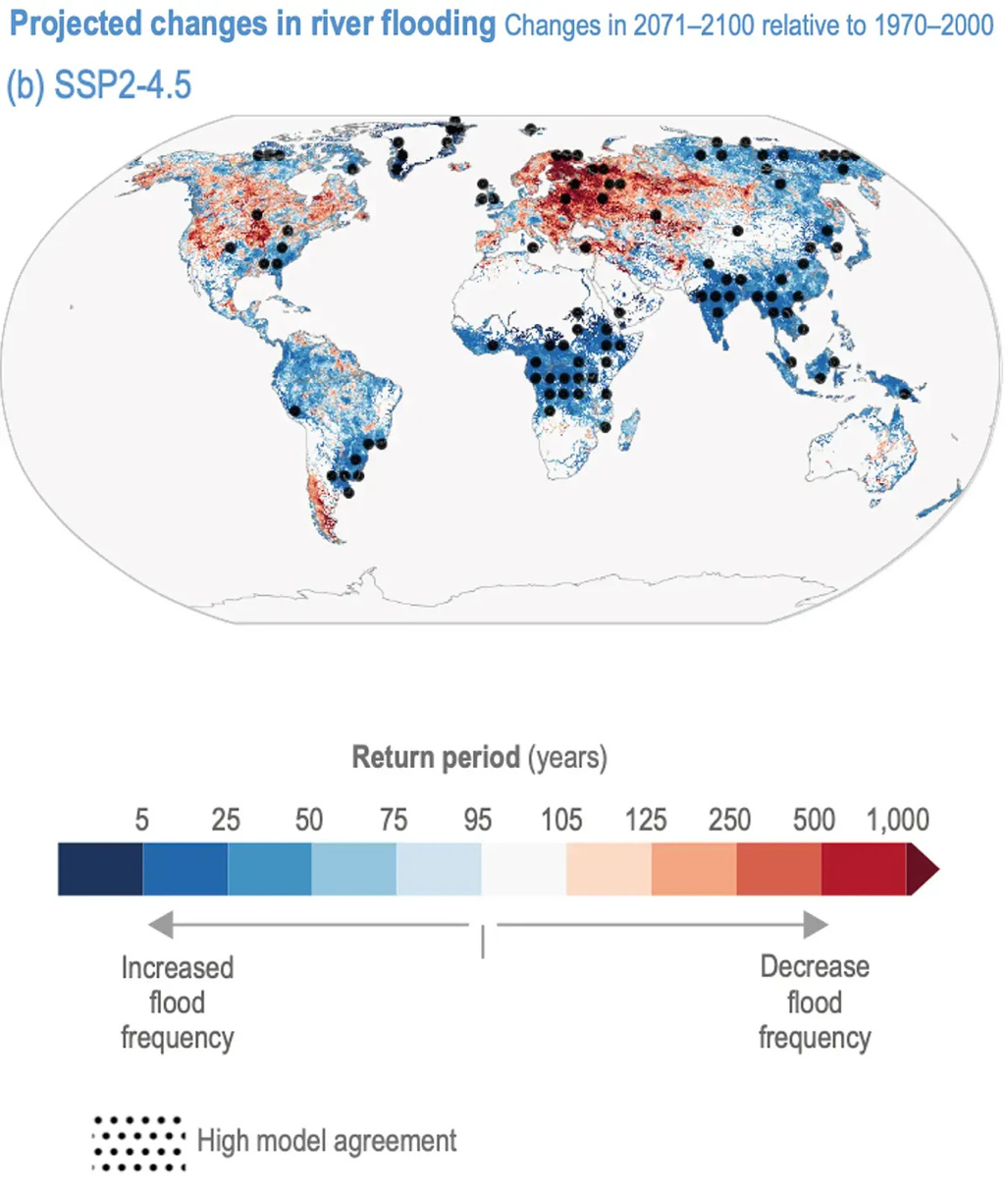

3. Projected floods

Source: IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

For the long run (2071-2100), we can see increased projected floods in southern Brazil with high model agreement.

So yes, climate change may be a driver for more precipitation, and extreme rain, in Rio Grande do Sul, but there is a lot of uncertainty of when and how much.

We have a lot more certainty about exposure and vulnerability on the other hand.

Exposure

The very name of the state, translated as Great River of the South, speaks of exposure to water. It’s intuitive that a state established on a great river is exposed to hazards from the great river - river flooding.

One third of the municipalities of RGS are in the Guaíba (the great) river watershed, and most of its population: 38% of RGS population resides in metro Porto Alegre, a city built around the Guaíba. The city has a complex geography and hydrology, well explained by Caos Planejado.

In 1950, RGS population was 4 million and more than doubled to almost 11 million in 2022. The city of Porto Alegre (non-metro) grew from 272 000 people in the 1940’s (when the previous flood hit the city) to 1.3 million in 2022. Porto Alegre’s growth has happened on exposed land, some of it illegal.

Below official maps from RGS state government showing growth of metro Porto Alegre from 1973 (14 municipalities) to 2020 with 34 municipalities and high population density.

Here are pictures of Porto Alegre’s Iguatemi Shopping mall before and after construction in 1983, comprised of (water absorbing) farmland. Below it is the finished mall and built infrastructure, now surrounded by a sprawling city of concrete. Not only do we see more exposure, but also more vulnerable exposure: where does all the water drain?

Vulnerability

In 1941, also in early May, torrential rains his Porto Alegre and the Guaíba river rose to 4.76 meters (15 ft) above its normal level (see report here). A flood prevention system was designed and finished in 1970, comprised of a 2.6 km wall 3m high, 14 flood gates, 23 pump houses and 68 km of dikes.

During the 2024 floods, 19 pump houses failed and 1 flood gate collapsed flooding northern Porto Alegre. Four of the city’s six potable water treatment plants flooded and had to be shut down, leaving 70% of the population without water. Within the state of RGS, one dam collapsed six were at risk of imminent collapse (one remains at risk of collapse currently).

How did this happen?

The 1970’s flood prevention system was poorly maintained, and DEP agency responsible for maintenance has been losing funds and staff for decades. The agency responsible for potable water and sanitation was already underfunded and ransacked by previous (mis)administration. In 2023, the Mayor of Porto Alegre invested R$0 in flood maintenance and prevention, down from R$142 000 in 2022 and R$1.8 million in 2021.

In April of 2024, a federal disaster agency alerted the risk of a flooding disaster in Rio Grande do Sul. In 2021, on the 80th anniversary of Porto Alegre’s historic flood, climatologist Pedro Valente warned about the risk to floods.

Unsurprisingly, it is the poor (often most vulnerable) who bear the brunt of disasters. Here’s a map of flooding in 2024 and income in Porto Alegre. The wealthy, for the most part, were spared, the poor pay the price (salario minimo means minimum wage, in 2024 =US $282).

The lead actor/actress

After all this we can ask: Who is the lead actor/actress in RGS floods?

Let’s refresh with the full cast of characters illustrated and described below.

Underlying disaster risk drivers — also referred to as underlying disaster risk factors — include poverty and inequality, climate change and variability, unplanned and rapid urbanization and the lack of disaster risk considerations in land management and environmental and natural resource management, as well as compounding factors such as demographic change, non- disaster risk-informed policies, the lack of regulations and incentives for private disaster risk reduction investment, complex supply chains, the limited availability of technology, unsustainable uses of natural resources, declining ecosystems, pandemics and epidemics. National Disaster Risk Assessment, 2017. Fig 3. Pg 29.

There is no magical mathematical or scientific answer to identifying a lead actor (though disaster normalization gets pretty close). Human reason must assess all information, based on the best available scientific, economic, social and historical data, and make a judgement.

In my estimation, climate change has no chance of being considered for lead actress/actor for RGS floods. The hazard - whether driven by climate or natural variability (El Niño) - plays a secondary role to exposure and vulnerability.

RGS state and city of Porto Alegre are exposed to flooding. Since the catastrophic 1941 flood, Porto Alegre’s population grew by almost 1 million and its flood prevention system was outdated and poorly maintained.

Vulnerability, driven by incompetence and possibly corruption, the bread and butter in Brazilian public administration and a national export, are the top contenders in my book.

Climate change is the best supporting actor of all times.

While the media sells climate as the Katherine Hepburn of disasters (the most best actress awards), in reality climate change is Walter Brennan (the most supporting actor awards).

Never heard of Brennan? That’s my point. Hepburn, rightly, deserves all the attention. Don’t be fooled.